BY BONNIE ROBINSON

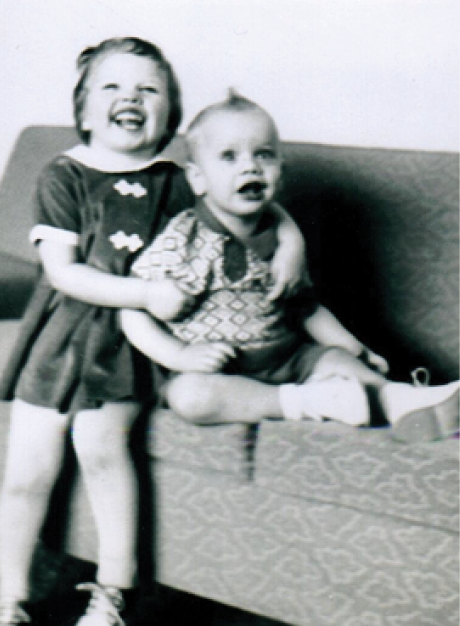

The last time I saw my brother Randy Zohner, he had travelled to Powell River for a visit.

After a great afternoon, Randy returned home to work at the Bamfield Marine Science Centre, where he was the cafeteria manager. A few weeks went by. The next thing I knew, I was notified Randy was dead and a police investigation was under way.

His body was taken to forensics in Vancouver and not released until after the autopsy. I felt helpless as I waited for more information about what had happened. In the meantime I was confronted with his face on the TV news, in newspapers, and on Facebook.

Adrenalin kicked in and I began to run on auto-pilot. I travelled to Bamfield Marine Science Centre where the community held an amazing memorial for Randy and letters and cards flooded in from so many people. In the meantime, we were planning our own memorial for family and friends in our community here in Powell River – where Randy grew up.

Police laid a manslaughter charge against the man accused of killing Randy. This was the beginning of a long journey in a criminal justice system that has not changed for many years.

I was connected to Tamara Cocco from RCMP Victim Services in Port Alberni to provide emotional support – while going through this trauma.

Shock, anger and numbness is what I felt as a victim.

I was becoming exhausted quickly while making frequent trips to Port Alberni to meet with Crown Counsel, David Kidd. More news – Randy’s case got moved to the Regional Deputy Crown Counsel in Nanaimo. We yet again travelled to Nanaimo to meet Glen Kelt. It was at this point that there was a new concern about Randy’s case and we were advised it would not move forward at this time.

Tamara saw our devastation. She offered an opportunity for us, Randy’s family, to meet the man accused of killing him.

It was here that I learned of a movement to seek justice for crime differently.

I had unanswered questions about what happened. And, I had questions about the man who did it. To this point I had felt helpless in the criminal justice system – but now I was being offered a voice. I had been trying to advocate for the deceased and now – for the first time since this nightmare began – I had an opportunity to play a role.

The accused was also asked if he would attend a meeting with the victim’s family and – surprisingly – he said yes. This opened doors as I learned he had been feeling horrific pain with the choices he made in the moment of Randy’s death.

There were phone conferences with professionals in preparation for this supervised meeting. I had a supporter who attended the meeting with me.

We met in a neutral location planned by Tamara and her team. The meeting was conducted by the professionals and supervised throughout in a safe setting. The accused was asked to speak first and tell what had happened up to the point of Randy’s death. His sister was on speaker phone as part of the meeting and said, “Our whole family is hurting for the pain our brother has caused you and yours,” and a light bulb went on for me. I remember noting that so many people were affected by this one person’s death – on both sides, accused and victims.

The trance I had been living in was lifted. Something great was happening in this meeting. I was understanding that this man had made poor choices. He had an opportunity to explain in his own words to me the circumstances surrounding Randy’s death.

Next came my turn. I looked into the eyes of the offender and then took a deep breath. I gave him a letter from my heart on how I felt and how our family chain was broken. For the rest of my life nothing would ever be the same. A link was now missing. There is a big gap between me and my younger siblings. My parents were heavily grieving and trying to understand. I had a voice. How could the accused understand my pain without understanding what he had done? It was a huge relief to be able to tell him how I felt.

During the last part of this meeting, I was able to request that the accused go to AA, see a counsellor and try and live the rest of his life as a better person in society. I do not believe that jail time would actually better this person. I was able to offer solace to the accused – something no other person involved from the outside could do. Rather than punishment, justice was served through the beginning stages of healing.

This was the first moment of grace I had felt through this journey.

Can I forgive? I struggle with that. I still remember clearly the circumstances – but now I can move forward rather than stay stuck.